Operation Legacy: How the British government destroyed its history

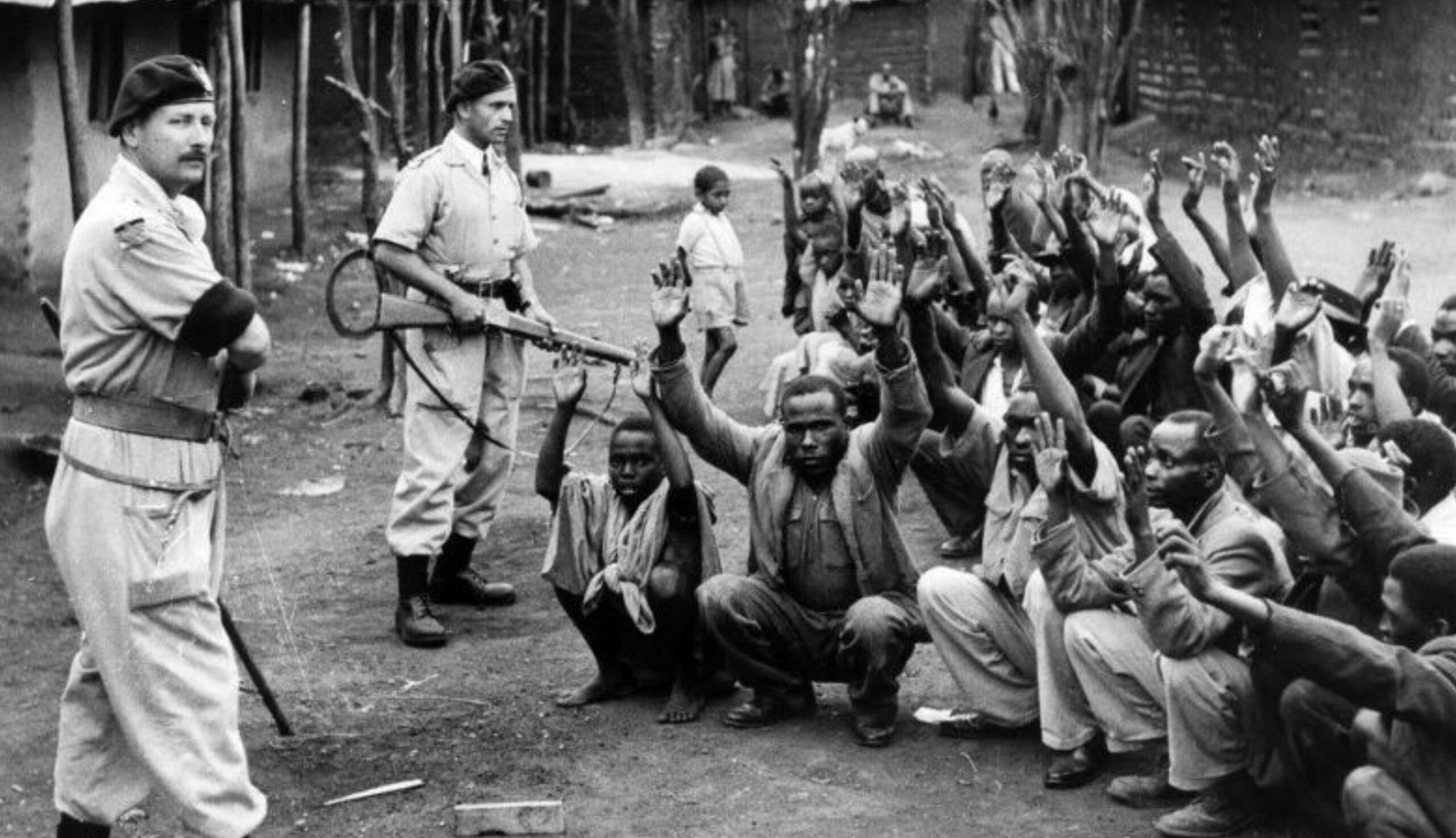

In 2011, after a legal fight that lasted more than ten years, a group of Kenyans tortured by colonial authorities won the right to sue the British government. The four complainants, selected from among 6,000 depositions, had all been imprisoned in concentration camps in the 1950s and subjected to appalling abuses. Ndiku Mutua and Paulo Muoka Nzili had been castrated; Jane Muthoni Mara had been raped with bottles filled with boiling water; and Wambugu Wa Nyingi survived the March 1959 Hola Massacre, in which camp guards beat eleven detainees to death, leaving seventy-seven others with debilitating injuries. For years, the British government denied the events, and also denied the existence of any records that would corroborate them, along with the rights of former colonial subjects to challenge their oppressors following independence. Once the last of these objections was overturned by the High Court in London, the government was forced to admit that it did indeed possess such documents – thousands of them.

“Common torture tactics included starvation, electrocution, mutilation, and forcible penetration”

Known as the ‘migrated archive’, a huge cache of colonial-era documents was stored at secret sites around the UK for decades, its existence unknown to historians and denied by civil servants. At Hanslope Park in the Midlands, a secretive government research facility, around 1.2 million documents revealed details of the Kenyan ‘pipeline’ system, which historians compared to the Nazi concentration camps. Thousands of men, women, and even children suffered beatings and rape during screening and interrogations. Common torture tactics included starvation, electrocution, mutilation, and forcible penetration, and extended to whipping and burning detainees to death. The files also contained details of colonial activities in at least thirty-seven other nations, including massacres of villagers during the Malayan emergency, the systemic subversion of democracy in British Guiana, the operation of Army Intelligence torture in Aden, and the planned testing of poison gas in Botswana.

The migrated archive also contained evidence that it was only a small part of a much larger, and largely destroyed, hidden history. Accompanying the remaining files – most of which have still not been released – are thousands of ‘destruction certificates’: records of absences that attest to a comprehensive programme of obfuscation and erasure. In the dying years of the British Empire, colonial administrators were instructed to gather up and secure all the records they could, and either burn them or ship them to London. This was known as Operation Legacy, and was intended to ensure the white-washing of colonial history. Government offices, assisted by MI5 and Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, either built pyres or, when the smoke became too obvious, packed them into weighted crates and sunk them offshore, in order to protect their secrets from the governments of newly independent nations – or from future historians.

“the top secret independence records simply disappeared”

Even when incriminating evidence survives for decades, it isn’t safe. Until 1993, a collection of 170 boxes of documents flown to Britain as part of Operation Legacy were stored in London, where they were marked ‘Top Secret Independence Records 1953 to 1963’. According to remaining records, they took up seventy-nine feet of shelf space in room 52A of Admiralty Arch, and included files on Kenya, Singapore, Malaya, Palestine, Uganda, Malta, and fifteen other colonies. A surviving partial inventory notes that the Kenyan files included documents about the abuse of prisoners and about psychological warfare. One batch, entitled ‘Situation in Kenya – Employment of Witch Doctors by CO [Colonial Office]’, carried the warning, ‘This file to be processed and received only by a male clerical officer.’ In 1992, perhaps afraid that a Labour victory in the upcoming general election would lead to a new period of openness and disclosure, the Foreign Office ordered thousands of documents shipped to Hanslope Park. In the process, the top secret independence records simply disappeared. No destruction certificates were issued, and no record has been found in other archives. By law, the documents should have been transferred to the National Archives, or their further classification justified, but instead they were simply expunged from the record. Historians have been forced to the conclusion that, fifty years after the events they documented took place, the only remaining records were destroyed in the heart of the British capital.

“Operation Legacy was a deliberate and knowing effort to obscure the violence and coercion that enabled imperialism”

The brutality in Kenya was ‘distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or communist Russia’, wrote the colony’s own attorney general to its British governor in 1957. Nevertheless, he agreed to write new legislation permitting it, as long as it was kept secret. ‘If we must sin, we must sin quietly’, he affirmed. Operation Legacy was a deliberate and knowing effort to obscure the violence and coercion that enabled imperialism, and its manipulation of history prevents us from reckoning with the British Empire’s legacy of racism, covert power, and inequality today. Moreover, the habit of secrecy it engendered permits its abuses to continue into the present day. The torture techniques developed in colonial Kenya were refined into the ‘five techniques’ deployed by the British Army in Northern Ireland, and then into the CIA’s ‘enhanced interrogation’ guidelines. In 1990, the police archive at Carrickfergus, which contained vital evidence regarding the actions of the British state in Northern Ireland, was destroyed by arson. Evidence increasingly links the fire to the British Army itself. When investigators tried to establish whether CIA rendition flights had stopped over on the British territory of Diego Garcia, they were told that the flight records were ‘incomplete due to water damage’. It’s hard to think of a more apt, or horrible, excuse: having failed to cover up its waterboarding of detainees, the intelligence agencies resorted to waterboarding information itself.

Looking back over this litany of deception suggests that we have been living in a dark age for quite some time, and there are signs that contemporary networks are making it harder to hide the sins of the past – or the present. But for this to be true, we would have to be getting better not only at spotting the signs of obfuscation, but also at acting to curb it. As the torrent of revelations about global surveillance practices released over the last five years have shown, awareness of this corrosion rarely translates into remedy.

—

James Bridle is an artist, writer and publisher based in London. He kindly offered us an extract from his recent book, New Dark Age, to be published as part of the Ghostwriter series. Purchase a copy of James Bridle’s ‘New Dark Age’ here.

This is a Ghostwriter article.

Ghostwriter is a space where people from any background can contribute their thoughts to the discussion of culture, politics and identity. Read more