Voodoo in My Heart: a brief history of Haitian zombies

To complement my latest short film, I wanted to share some of the inspirations behind its conception. Voodoo in My Heart follows the story of Emily, who, after being bitten by her zombie boyfriend, must learn about the history of Haitian Vodou if she wants to survive. By no means is the film solely about the history of zombies, and by no means am I an expert on any of this stuff. But for anyone generally interested in the origin of the zombie myth, hopefully this article provides some interesting insight about zombies that you never thought you’d know. Much of this writing is copy and pasted from my MPhil thesis so please excuse some of the academic jargon.

Made in Haiti, Sold in America

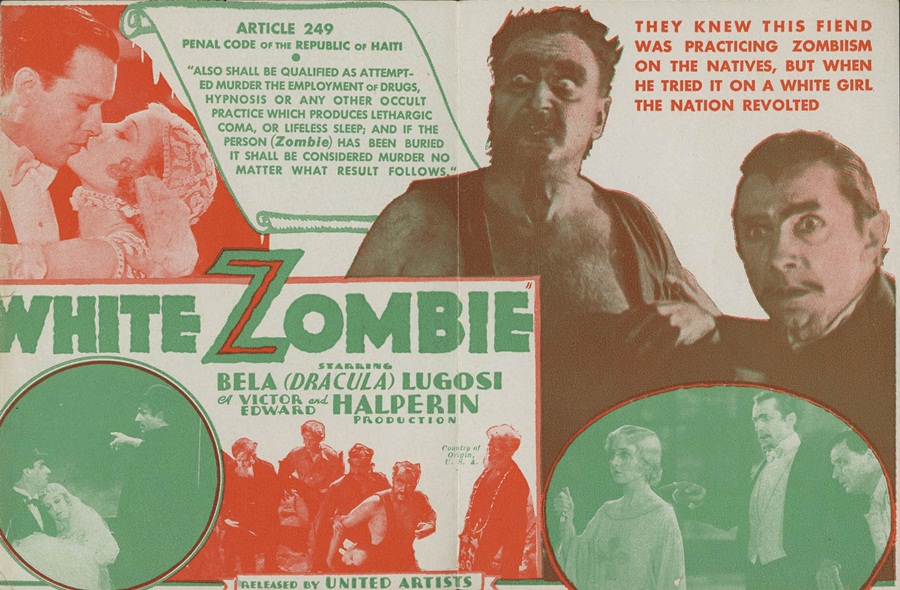

Unlike Dracula and Frankenstein, the “zombie” has a non-European origin. The zombie is a figure that has its origins in Haitian Vodou, a hybrid religion born from the intermixing of various African cultures during transatlantic slavery. With virtually no known literature that trace its origins, the zombie myth was appropriated and transformed by Western imaginations. William Seabrook’s The Magic Island is credited as making the first significant reference to the Haitian zombie and popularising the creature in the United States. In a chapter titled ‘Dead Men Working in the Cane Fields’, Seabrook describes the zombie as ‘a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life.’ Three years after the book’s publication in 1929, the first official zombie movie, White Zombie (1932), was released in US theatres.

Seabrook’s book largely portrayed Haiti as a perverse fantasy that stimulated and reinforced the old prejudices of slavery. Because of Seabrook’s constructed fantasy, the zombie came to be represented in early Hollywood as a slave-like corpse that followed orders from a voodoo master. However, this popular representation of the zombie in the US often made no reference to the historic legacy of the zombie as a product of slavery-era Vodou.

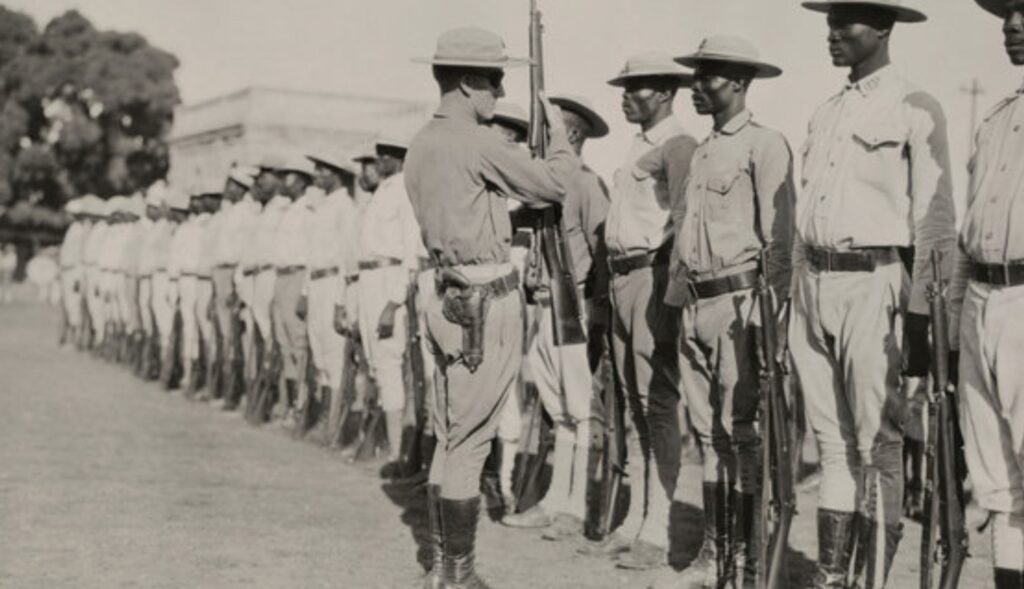

In Haiti, History, and the Gods, Joan Dayan illustrates the connection between the zombie myth and transatlantic slavery using her knowledge of Haitian Vodou, while also briefly highlighting the role of the US occupation of Haiti between 1915 – 1934 in exoticizing the zombie. Dayan emphasizes that ‘the zombie tells the story of colonization’ and as a ‘soulless husk deprived of freedom – is the ultimate sign of loss and dispossession.’ Importantly, Dayan highlights how the fear of enslavement and the fear of becoming a zombie intertwine.

Other scholars have chosen to place more importance on the US occupation of Haiti in forming their understanding of the zombie, but in many ways the two are inextricably connected. For example, the zombie’s transportation to US popular culture in the 1930s happened alongside the Great Depression, thus in some ways, the zombie, as a figure of enslavement, became particularly resonant to thousands of ‘dispossessed’ Americans who had recently been made aware of how powerless and slave-like they were in a capitalist system. But most significantly, zombie movies of the 1930s portrayed Haiti as barbaric and primitive, thus helping to justify the “civilising” force of the US military.

What is a Zombie?

Before delving into the context behind the zombie figure, it’s important to acknowledge that the definition of the zombie has been the subject of scholarly debate. The Haitian creole translation of zombie is actually “zonbi” – scholars such as Elizabeth McAlister have chosen to use the latter to describe the Haitian figure. “Zombie” was Seabrook’s choice of spelling which is likely why it is the most common spelling today.

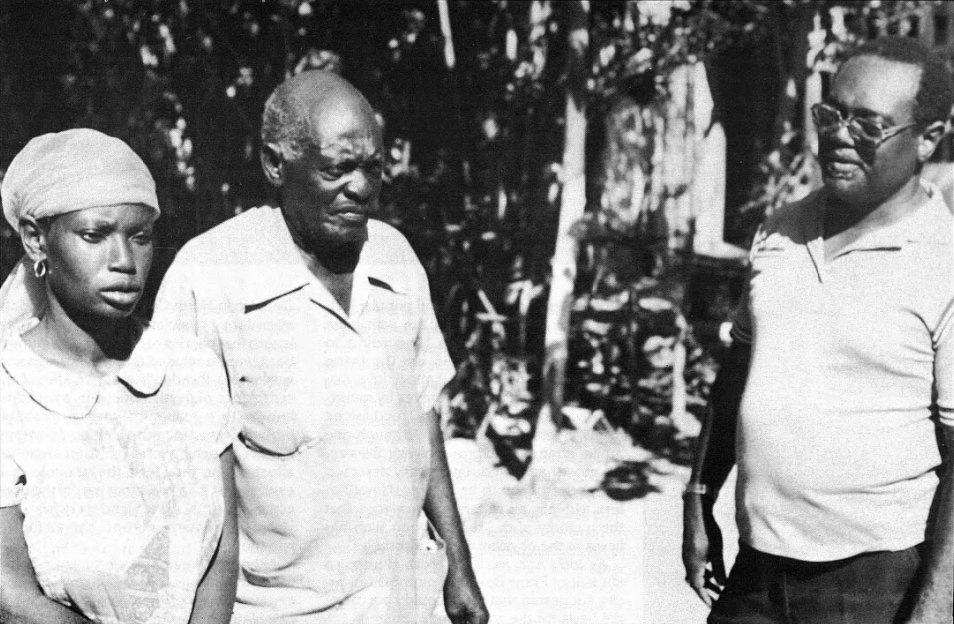

Zora Neale Hurston writes that zombies are ‘bodies without souls; the living dead.’ This description aligns comfortably with the movie monster, while anthropologist Alfred Metraux’s slightly more complex definition explains, ‘zombi are people whose decease has been duly recorded, and whose burial has been witnessed, but who are found a few years later living with a bokor (sorcerer) in a state verging on idiocy.’ Metraux’s definition describes zombies as ‘people’, which appears to be a far more humanistic description than the ‘living dead’. Metraux’s definition also aligns with the famous case of Clairvius Narcisse – a real victim of Haitian zombification. If you want to creep yourself out, check out Narcisse’s story.

In Passage of Darkness, Wade Davis provides a slightly more illuminating definition of the zombie: ‘The … victim of zombification suffers a fate worse than death – the loss of individual freedom implied by enslavement, and the sacrifice of individual identity and autonomy implied by the loss of the ti bon ange.’ Interestingly, Davis acknowledges the Vodou doctrine proposal that all people are made up of two souls; the “gros bon ange” (big good angel – an undifferentiated energy that functions to keep the human body alive) and the “ti bon ange” (little good angel – the source of an individual’s personality, character and willpower).

Hurston’s definition of the zombie suggests that no soul inhabits it because the zombie is dead, implying that humans, as such, only possess a single soul. This definition solidifies the zombie as a miraculous product of unnatural black magic; the prominent theme in early Hollywood zombie films. Metraux’s approach accepts that the zombie suffers from psychological impairment but does not address matters of the soul. Davis, however, encourages further elaboration by acknowledging the aspect of ‘enslavement’ necessary for zombification, while also highlighting the removal of ‘individual identity’. Davis underlines the significance of the ritual responsible for creating the zombie, allowing us to appreciate the zombie as a product of something as important as the figure itself. Thus, perhaps zombification is not simply about the production of mindless zombies but instead, it is about a process involving a sorcerer or a master and the erasure of an individual’s identity.

The Power of the Zombie

Despite the Haitian zombie’s appropriation by early Hollywood cinema, and despite the fact that the zombie can therefore be perceived as a racist vilification of a ‘barbaric’ people, there is also a lot to be said about the power implicit in the zombie’s history. As articulated by Sarah Juliet Lauro and Karen Embry, the zombie narrative is, in some ways, a reprisal of the Haitian Revolution and a story of slave rebellion. They further elucidate that in spite of the Haitian rebels throwing off the yoke of colonial servitude, Haiti has had an unhappy national history, plagued by foreign occupation, civil unrest, and disease, therefore the zombie embodies this disappointment in some way. Lauro and Kembry explain that the zombie ‘only symbolically defies mortality, and woefully at that: even the zombie’s survival of death is anti-celebratory, for it remains trapped in a corpse body.’

Frank Degoul understands zombification as a defence mechanism of sorts, describing it as ‘a practice that scared the [outsiders].’ Degoul implies that the fear of zombification displayed in US literature and cinema had been confirmed by the experiences of US troops in Haiti during the occupation. Furthermore, this fear of zombification reflected Haiti’s mysterious power amid the neo-colonial effort by which US hegemony had attempted to establish itself in Haiti between 1915 – 1934. Therefore, zombie films in early Hollywood cinema attempted to represent this fear in a way that placed Haiti as primitive and barbaric, hence powerless, despite the power in the zombie figure’s history.

Drawing from her ethnographic work in Haiti, Elizabeth McAlister argues that the zombie is entwined with the mystical arts that have developed there since the colonial period, and comprises a form of myth-making that represents, responds to, and mystifies the fear of slavery, collusion with it, and rebellion against it. Maya Deren’s famous work on Haitian Vodou fails to mention much about the zombie figure, yet she does mention that they function as vehicles for ‘uncomplaining slave-labour.’ This opens up an interesting inquiry into McAlister’s suggestion of collusion. If the zombie is ‘uncomplaining’, is it colluding with slavery? It’s very possible that this uncomplaining nature of the zombie is what appealed to early Hollywood as a means of placing a revolutionary nation back into a context of submission and obedience.

I Walked With a Zombie (1943) and The Ghost Breakers (1945) are two of the only early zombie films that actually mention slavery. In The Ghost Breakers it is hinted that the ghouls that possess the protagonist’s castle are vengeful spirits who suffered under the slave trade. Whereas in I Walked With a Zombie the curse of slavery is clearly mentioned as a reasoning for the “sadness” existing on their island. In the latter film, a white female character has clear racist attitudes towards the “native nonsense” of the blacks, yet she is guilty of trying to utilize the power of voodoo herself. Unlike the other zombie films, two white characters in I Walked With a Zombie die after being chased into the ocean by a black zombie played by the tall and intimidating Darby Jones. In some ways, voodoo is the triumphant winner in the story. The film’s message almost serves as a warning for white people not to mess with voodoo; an ancient African spiritual power, not merely “native nonsense”.

Zombie Sexuality

More recently, authors such as Chera Kee and Eric King Watts have chosen to explore zombies within the context of sexuality and post-racial fantasies. Whereas Watts enquires into the black body as a ‘bio threat’ unleashed onto white populations, Kee highlights the intention of shutting down symbolic interracial fantasies in the early zombie films. Similarly, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert acknowledges the racial context behind the early zombie films by pointing towards the US laws against interracial sexual relations. Paravisini-Gebert suggests that the early zombie films transposed the realities of sexual relationships between races into dangerous black male lust for white females. Edna Aizenberg also notices this displacement in early zombie films, but takes it further by arguing that insecurities related to interracial sexual relationships are responsible for the lack of honest analyses of early zombie films.

Kee argues that ‘Voodoo zombies, then, either on a cosmetic level as pale black bodies or on a psychological level as the white body corrupted by black magic, are visual/performative displays of miscegenation—of the mixing of black and white cultures in an enslaved body.’ This more recent work provides a refreshing outlook on the analysis of the zombie through the cinematic lens. It is evidently clear in early zombie films that zombies were contaminated by voodoo or “black magic”, relying on the idea that blackness signifies a chaos that only white men can subdue.

By displaying young, white Americans traveling to the Caribbean, encountering a foreign culture that threatened to possess them through zombification, Kee argues that early zombie films could play with issues of interracial sexual desire without openly dealing with sexual relationships between black and white bodies. Yet, the only reason these films could toy with such fantasies is because they provided a remedy for zombification, or at least an escape from it. Early Hollywood showed us that ‘white bodies could be corrupted by zombification and then be rescued from it’ which in turn, reaffirmed the racial status quo in US society and maintained a portrayal of Haiti and its culture as backwards.

In Zombies on Broadway (1945) the voodoo master’s black zombie is clearly positioned as a sexual threat to the white female character, whereby in one scene he appears in her room shortly after she has undressed. However, the zombie ends up being an anti-hero of sorts when he kills his white voodoo master so there are conflicting messages in the film about what the black zombie represents. Is he a danger to white women or is he a benevolent hero who frees himself from slavery? The answer is unclear. What is clear is that Zombies on Broadway represents an accumulation of the themes in the zombie films that preceded it, and cements the zombie as an integral part of the US entertainment industry.

All of the old voodoo-zombie films are fascinating from a historical point of view. They are all worth a watch, especially I Walked With a Zombie. Ouanga (1935) is also a particularly strange film, and according to Sheldon Leonard’s account of its production, three crew members died during the process, and the property master stole voodoo relics from Haiti to be used as props in the film.

If you watched my film, I hope you enjoyed it and now have a better understanding of why I felt compelled to make it. I’m all for the crazy, cannibalistic Walking Dead zombies, but hopefully we see more Jordan Peele-esc zombie films in the future, exploring the true origins of the genre.