From Arthur to Obama: How Race Shaped My Identity

When I was younger I was part of an exclusive club of which there were only four members. Out of almost 180 kids in my year group at school, only four of us were not white. I had largely been ignorant to the concept of race until I was forced to confront it in my white school, my white village and with my white friends. While the world always had no problem defining me by race, it took a little longer until I was comfortable defining myself in that way. This article is a brief, whistle-stop tour of my racial identity and how it led me to a path of self-discovery.

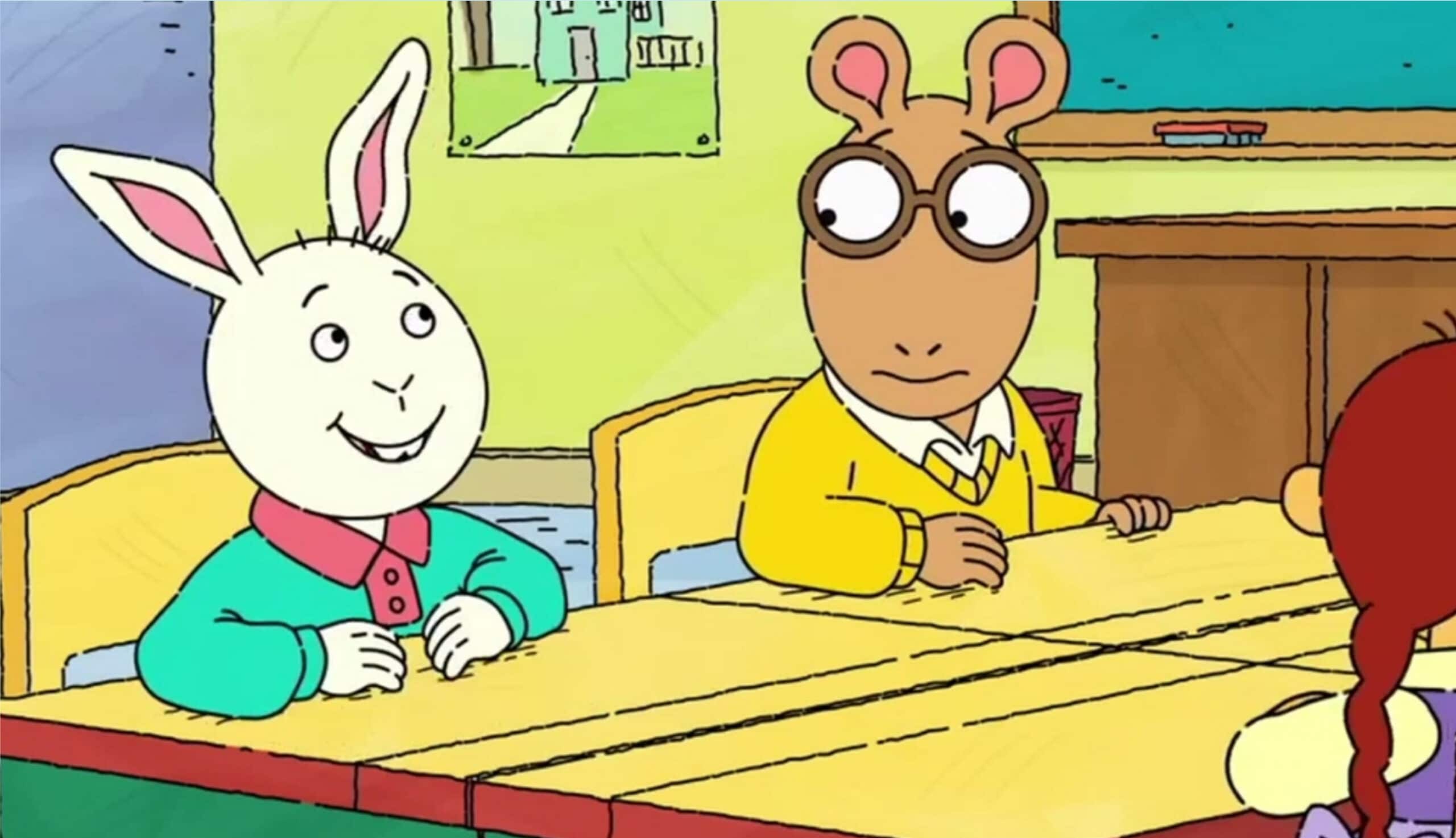

The earliest memory that I can distinctly recollect about race and how it related to my own identity was while watching Arthur, the children’s cartoon series. Despite it being one of my favourite TV shows because yes, it was quite frankly amazing, I also pointedly related to Arthur’s character for another reason. His skin was the same colour as mine. I shan’t dive into the implications of how the one character I related to on TV was an animal and the relation that might have to society’s historical attitudes towards black people – but it is worth pondering. When the yellow aardvark sang about library cards, I felt an odd familiarity with him. But at the time, I still didn’t quite understand how my own skin colour was affecting my subconscious thoughts.

“I was surrounded by white people to whom race was not a thing they considered or thought about.”

My race was something I discovered at school like a blind lamb in the hands of an inexperienced shepherd – (word to Kojey Radical for the metaphor). There was no one to help me through it or to share the similarities of their own experiences with mine. I was surrounded by white people to whom race was not a thing they considered or thought about. Their ‘race’ was the norm. In British society whiteness has always been the norm. Post-Windrush, during the mass-migration of people of colour to the UK, there was a significant effort to ensure that being British was synonymous with being white. There was a genuine effort to enforce this idea and to remind us brown migrants and the children of these migrants that we weren’t British – that we were deviations from the norm. Chris Waters writes about this in Dark Strangers in Our Midst. Moreover, the British Nationality Act of 1948, granting people of colour from British colonies equal citizenship in the UK, was undone by 1971 with an immigration act that offered more freedom to white ‘patrial’ migrants from Canada, New Zealand and Australia than it did to their darker-skinned counterparts.

In an all-white school, I didn’t understand what it meant to be black. There was no sudden turning point in my quest to inadvertently discover my own race and no eureka moment. There was only a very gradual shift, lots of grey areas and plenty of racist jokes. “Oh but it’s a joke! Chill! It’s banter!” is the reply I heard at school to my protests. Whether I liked it or not, the jokes also helped to define my own race, specifically around the time of Barack Obama’s 2008 election. I remember a particular joke that was the straw that broke the camel’s back for me and led me to express my frustrations through writing; “If Barack Obama came to town, Kieren would have to speak to him because no one else would understand him”. Monkey noises followed. This joke reminded me that even the status of being president of the most powerful country on Earth could not protect a black man from being below whiteness. As harmless as a joke might seem, they reinforce ideas. They made me feel as though whatever I did, I’d always be below all white people. They reinforce vicious ideas and stereotypes that see us as criminals, as stupid and lesser.

The next stand-out memory of my conceptualization of race was a video a few years later, brought up in a PSHE lesson, called ‘Rappin’ for Jesus’. I can’t stress how angry this video makes me. Two old white people rap about how Jesus is their ‘nigger’. Firstly, the n-word is obviously a contentious issue so to have two white people saying it and thinking it’s alright to put on YouTube is one thing. But to also put the word into a rap is to take the ultimate dump on black culture – implying that rap music is the only language we understand. Then on top of that, the fact that my entire class burst into laughter and ignored my protests was like salt being scrubbed into my wounds. It was very indicative of common attitudes towards race in a white suburban town; pretend it’s not a problem, ignore the young boy telling you it is, his anger and his pain, and just keep laughing. The paleness of their skin permitted their ignorance; a privilege for them and an impossibility for me.

“When I confronted my white friends about their racist language, they did seem remorseful and legitimately unaware of how their words had hurt.”

The list of these types of events go on. A hip-hop room at my local club was often called the ‘nigger room’. Some of my closest friends, knowing I didn’t like the n-word, would happily say it behind my back. These friends were not evil people. But without a true understanding of how people of colour feel about racism and racist language, they wouldn’t know any better. When I confronted my white friends about their racist language, they did seem remorseful and legitimately unaware of how their words had hurt. But they had hurt and the damage had been done. The formation of my conception of race was largely out of my control. It was a never-ending slog of fried chicken and basketball jokes, of comparisons to literally any black person ever, of an isolation to my friends because in some way, on some level they wouldn’t ever fully understand me as the black kid in a white school. The formation of my race ranged from children’s cartoons, jokes about Obama and two old white people trying to rap. All these experiences had one thing in common; they were defined by the colour of my skin.

Sure, black people do not suffer physical pain at the hands of white people as regularly as we used to. We aren’t lynched, strung up from trees or hunted down in the streets as we once were. But exceptions like Stephen Lawrence or Mark Duggan prove that our physical safety can still be a pertinent issue. In truth, the legacy of this violence survives in our minds. It lingers in the childish name-calling and the seemingly harmless jokes. This reinforces ideas created decades ago including toxic stereotypes that cause the police to stop us disproportionately. These racial micro-aggressions that are intrinsically a part of people’s everyday behaviour can have a massive effect on the mental health and wellbeing of people of colour. However, we are not the exclusive victims of micro-aggressions. Women, the LGBTQ community, the physically disabled, the mentally ill and even straight, able-bodied, white men suffer them.

The stigmas and prejudices that exist in our world can only be combatted by having an open and honest conversation about them. We must look our own demons in the eye, acknowledge their existence and stop pretending our closets are free of skeletons. The feelings of isolation I have spoken about can be confronted by communication between people from all walks of life. We need to bring all of our different perspectives to the table if we are to move towards a better world.