A Brief History of Mixed-Race Identity

Author’s note: I’ve spoken of black/white mixed-race identity throughout because it is what applies to my own personal experiences but what I speak of (studies and all) may also apply to all people of multi-ethnic origin.

The concept of mixed-race identity, as we understand it today, is quite a modern one. Historically speaking, mixed-race identity of black/white origin stems largely from colonial history and the interaction between slave-owners and slaves. Due to the nature of slave society, these weren’t always pleasant interactions. Mixed-race children during the transatlantic slave-trade era were often the product of white slave-owners raping black slaves.

The complexity of the black/white mixed-race identity has its origins in the disturbing invention of the ‘one-drop rule’; a rule that ensured mixed-race people stayed firmly on one side of the black-white divide. This was a simple idea, prominent in the United States, stating that one drop of black blood in a person ensured legal and social treatment as a black person however mixed or light-skinned they may look. This was of course an arbitrary classification meant to ensure the continued enslavement of an entire people. Winant and Omi in their work ‘Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s’ attack the one-drop rule, pointing out the sheer impossibility of actually implementing it. Susan Guillory Phipps is a profoundly startling example of someone who tried to change their legal designation from black to white but ended up being refused because it was said she had 1/32 of black blood.

Illustration by Dom Culverwell

In England, the early origins of mixed-race identity were similarly fraught and often baffling by our modern standards with pseudo-science doing more harm than good. For an informative but digestible take on black British history, look to recent best-seller, ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race’. In this refreshing book, Reni Eddo-Lodge shines a light on a long forgotten history, including that of mixed-race children. In the early 20th century, mixed-race relationships were considered disturbing enough to warrant academic research, which in turn, influenced political rhetoric and action. In the 1920s, we were ‘wretched children’ according to the work of people like Rachel Fleming. Fleming’s work was influential not only in the political spheres of power but also in the public vernacular. Her work led to the cementing of the term ‘half-caste’; a word that I myself ignorantly used for much of my life, unaware of its origins or true meaning.

The work of Fleming and Liverpool University graduate Muriel Fletcher focused on the poorest mixed-race families in Liverpool and as such, found mixed-race children riddled with diseases and malnourished. This was because of their economic situation, not because mixed-race children were inherently sickly and ill. These children had their facial features categorised as ‘negroid’ or ‘English’ and Fletcher’s work reflected the very popular eugenics movement at the time. Mixed-race children were a result of ‘miscegenation’ and had ‘little future’.

For most of the 20th century, mixed-race relationships (and by extension children) were a problem to be stamped out. Barely a decade before my black Jamaican father and my white British mother were dating, a mixed-race couple were attacked on the streets of Liverpool by a white mob, just for being a mixed-race couple. This kind of thing was not unusual in the 70s. The police detectives claimed that the attack wasn’t racially motivated and no culprits were ever found. Eddo-Lodge writes about how this was one in a line of attacks similar to an earlier one at Latimer Road in London, 1958. An argument between a mixed-race couple led to a group of white men stepping in to protect the white wife, while a group of black men came to the husband’s aide. This led to three days of rioting and swastikas being painted on the doors of black families. This was happening within the lifetime of my parents; any one of these incidents could easily have happened to them.

So where do we fit in today? Do the ‘wretched children’ that fill some unknown grey area between the black and the white belong somewhere in the modern world? Studies on the mixed-race population suggest that the number in the UK could be anything from 800,000 to 1.2 million, with some figures suggesting as high as two million. Alas, it can be quite difficult to record accurate figures for the mixed-race population due to differing interpretations of what it means to be mixed-race.

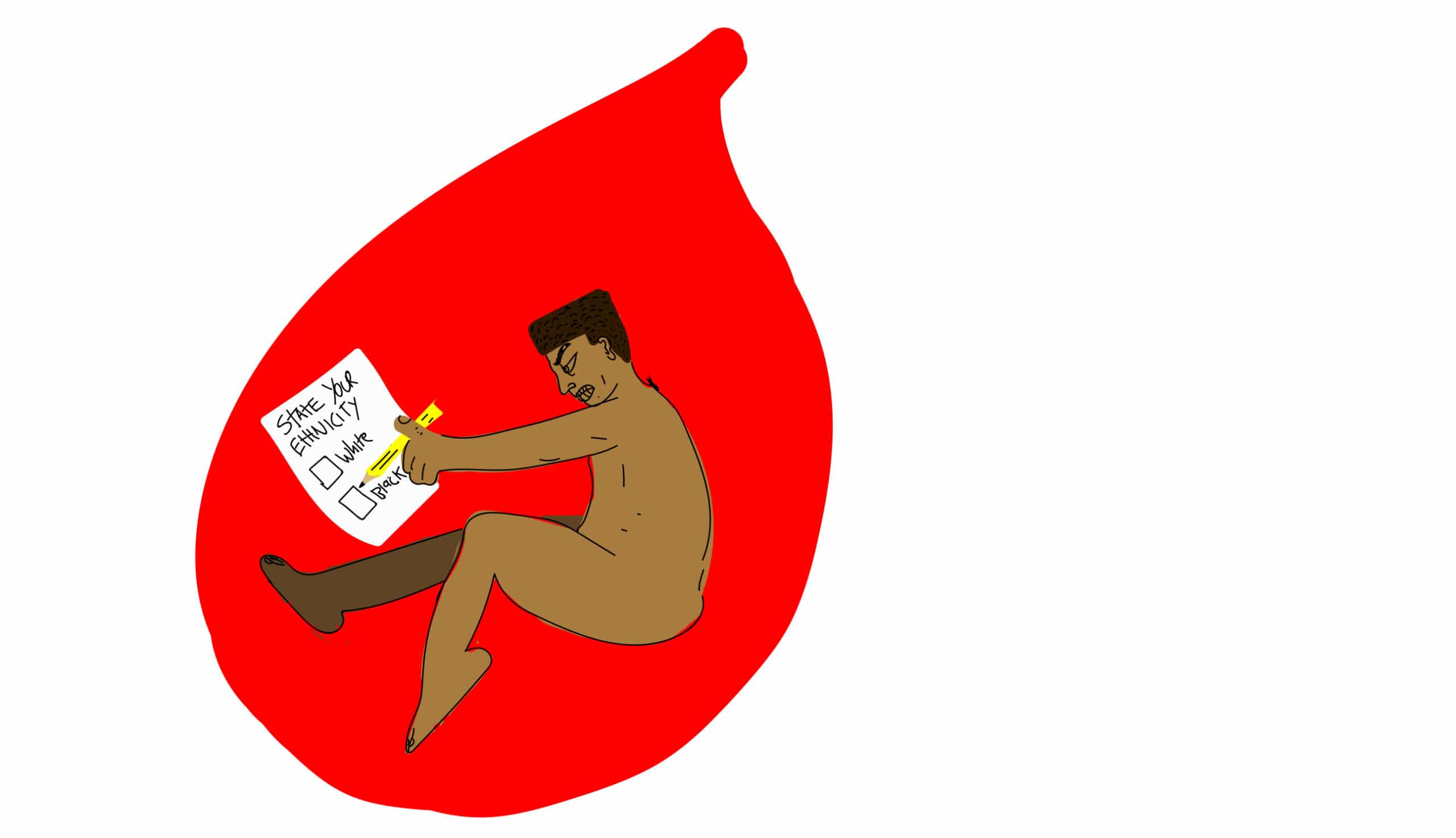

To me, this range and uncertainty in concrete statistics mirrors the uncertainty in our identity. We look at the endless boxes of the ethnicity forms and never totally know which one we should tick. For some, it leads to an identity crisis of sort; an odd dichotomy of certainty and ambiguity where you are deathly aware of what you are, as is the world, but you become also acutely aware that you don’t really know what that means. You’re not black or white and yet the ‘one-drop rule’ firmly situates you as black in the world’s eyes.

Illustration by Dom Culverwell

This deviation from white leaves you as black – and we certainly have more than a single drop. But that being said we’re still not black; not ‘fully black’ at least. I understand that this might sound like I’m moaning about semantics but it’s an incredibly important distinction in society’s perception of us as a group.

Peculiarly enough, this straddling of somewhere between black and white often seems to makes us appear more attractive. Jennifer Patrice Sims is one of many who has conducted studies and written articles exploring an inherent, internal bias towards the attractiveness of mixed-race people. She claims that there are a few simple reasons for this. Firstly, non-white people have a history of being deemed ‘exotic’ by white people. In our society, white is the norm. It is the centre line that everything else is judged off of. Mixed-race is not white; it’s an ‘exotic’ other and the ‘exotic’ is often deemed attractive or something that must be obtained. To be mixed-race is to deviate from the white norm – but not too big of a deviation. It’s foreign and exotic but at the same time it’s not too foreign and exotic. It’s acceptable. It’s not ‘black’, which for so long, as an idea, has been slandered and spat on in terms of beauty; black is the opposite of the beauty that mainstream culture often shows us – of white-blonde haired beauty.

Moreover, to have black/white mixed-race heritage is to benefit from straddling the unknown space in between black and white and yet to suffer from it as well – from fetishisation. Someone worth checking out on this subject is Homi K. Bhaba and his focus on fetishisation within the colonial discourse. Moreover we also suffer from the alienation from identifying with more than one (or none) of the concrete racial groups society espouses. Nia Ridgle is one of many to have written about this; she takes the example of Barack Obama who identifies as African-American despite being of mixed-race heritage. Whilst I don’t necessarily agree with all of her work, it is an interesting read.

Moreover, we must further expose the redundancy and arbitrariness of the racial categories that still affect our society today. The concept of biraciality raises awareness to the social racialisation of people; a relationship constructed in the immediate environment and context but not a fixed thing. This is an argument echoed by Laura Tabili in her article ‘Race Is a Relationship, and Not a Thing’ – a great take on race as a concept and how it manifests beyond a metaphysical level.

Despite being a growing group, the place and identity of mixed-race people is largely fluid and undefined in our society – often for the worse. But going forward, where does this leave us? In 2017, Lauren Jackson wrote a compelling article attacking the common theory that mixed-race people are evidence for the end of racism. The piece was in some ways a response to the release of Amma Asante’s film, A United Kingdom.

Image from ‘A United Kingdom’ (2016)

As once said on Blackish – award winning US TV show – “we’ll one day all be a shade of beige akin to Jesse Williams”. Nevertheless, I have to agree with Lauren Jackson and question this claim. The legacy of the one-drop rule ensures that we still definitively fall into the category of non-white and as such, face racism alongside the other issues I mentioned above. Our acceptance often stems from explicit racism itself. As I said earlier, we’re just white enough to be approved of but not white enough to be totally accepted. We’re held at arm’s length away while exalted for some things and dragged down for others.

The colonial systems which created the foundation for our Western world also created the racial system which led to me being labelled as mixed-race. These are not separate, independently operating strands. In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates highlights how racism is indistinguishable from America. For Britain, the legacy of our empire still massively influences our nation today. This legacy is one of racial genocides and human trafficking. The simple existence of and growth in the number of mixed-race people won’t undo the colonial legacy overnight. It won’t cause some giant shift in the discourse in public, political and academic spheres and rearrange how our society works on a social level.

Tim Wise’s ‘racism 2.0 theory’ is an amazing analysis of modern day racism. He points out how white people elevate certain people of colour to the level of equals – people they know personally or public figures like Barack Obama – yet studies conducted by Wise himself show that their opinions on the wider black population are still discriminatory. It provides an explanation for how America can vote for Barack Obama and then turn around and vote for a known racist like Donald Trump or how people can claim to have ‘black friends’ but still be racist.

I would love my existence to mean the end of racism; to have the world look at me and begrudgingly nod its head and laugh at its past crimes stretching back centuries across oceans and nation states alike. But it’s unrealistic and naive to think such a thing. If we all suddenly became mixed-race people then of course racism would struggle to thrive. Yet despite the great expansion of us as a group, we’re not growing as quickly as you may think. Many studies reveal how most people still date within their racial group. A recent study offered an explicit example, suggesting that only 9.4% of white people are willing to date people of colour. Furthermore, it’s unlikely that mixed-race relationships will manifest amongst all groups of people in our lifetime. We will remain a marginal group facing problems specific to us as we struggle to decide where we belong in this black and white world.

Whilst I do not think mixed-race people are symbolic of the end of racism, we are in many ways a sign of changing times and a reflection of the zeitgeist. The younger generations are continuing the work of those who came before. We are not afraid to challenge those who discriminate on the basis of race and we are not afraid to challenge the immoral policies of corporations and governments. Through publications like MANDEM and with writers and activists across the world, step-by-step, we are moving towards the end of institutionalised racism and to a world free from implicit racial bias. There will always be a few idiots – arseholes are universal – but it is my hope that my future mixed-race children will be able to celebrate and enjoy their existence while not feeling confused or anxious about their place in the world due to the colour of their skin.

To read more from Kieren check out his personal blog here: http://isaiahocean.blogspot.com/ Illustrations by Dom Culverwell https://www.instagram.com/domaculver/