Statues, Symbolism and National Identity

In the wake of the brutal murder of George Floyd, an overdue re-examination of statues and their significance as symbols of national identity has emerged to expose a problematic conversation. From slave traders to apartheid architects, colonisers to any other form of white supremacist, there should be little debate over statues that iconise those who exploited black people and engineered the machinery of systemic racism that prevails today. The way in which this fixation on statues has developed a dialogue around anti-racism, and the ensuing response, should not be ignored. Whilst the action of removing racist symbols is cosmetic to an extent, when considering the British context, the symbolism of statues is something that should be engaged with when re-evaluating nationalism, identity, and historical discourse.

Symbolism has been used as a tool to ground national identities since nationalism was conceived as a concept. From the French Revolution in 1789 to China’s transition from imperialism to a ‘unified’ country at the beginning of the 20th century, the totemic idolisation of national figures has been central to the development of identity within the nation-state.

When Edward Colston fell from his perch on the 7th of June, it marked the culmination of a series of events that can be used as an analogy for Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd. Bristol’s black community, from campaigners to historians, have used established communication channels to agitate the removal of Colston’s statue (amongst other mementos) since the 1990’s. This has been met with relative inactivity. A proposed plaque which detailed the extent of Colston’s role in the slave trade was subject to extensive debate, highlighting the unwillingness of certain groups of people to confront Britain’s historical racism and its pertinence today. In tearing down the statue, it is clear that civil disobedience was required to topple a symbol of the slave trade. Consequently, this has facilitated a broadened conversation around active anti-racism, leading to a re-appraisal of white supremacist statues and popular histories.

This is mirrored by broader narratives of anti-racism from the late 19th century through to the present-day. A one-way dialogue from primarily non-white communities has been met with the same inactivity and continued suppression of black rights activism. It is not difficult to see: continued mass incarceration of black men in America; the history of police brutality towards black people; the treatment of Colin Kaepernick; the Windrush Scandal; stop and search racial profiling. The list goes on.

As a result of the transnational direct action seen with the recent resurgence of Black Lives Matter protests, there has ostensibly been a shift in approaches to racial prejudices on an individual and institutionalised level. There is now a potential return to the NFL for Kaepernick, with the former pledging $250 million dollars to tackle systemic racism. Police officers are starting to be held accountable for the murder of black Americans presently and retrospectively – the minimum that is deserved. In the UK, the British Government have agreed to act on all recommendations in the Windrush Lessons Learned review following renewed external pressure. But there is still so much more to be done.

The overdue dismantling of Colston’s statue personifies the current zeitgeist. Statues that are symptomatic of a world built on oppression and discrimination are being re-evaluated across the globe. This has created space for a dialogue that centres on what these statues represent, in turn excavating broader issues such as the absence of colonial histories in state education. In engendering a conversation that needs to be had, it has also exposed a debate that is at times fuelling division rather than unity.

Events in Bristol caused a ripple effect. However, a re-assessment of certain statues that memorialise historical figures has at times been met with vehement opposition. In the UK, sections of the public see these statues as emblems of national identity, symbolising a nostalgic form of British exceptionalism that is underscored by imperialism. Considering the physical manifestation of history that the statues in question portray, this is an idea that needs to be challenged.

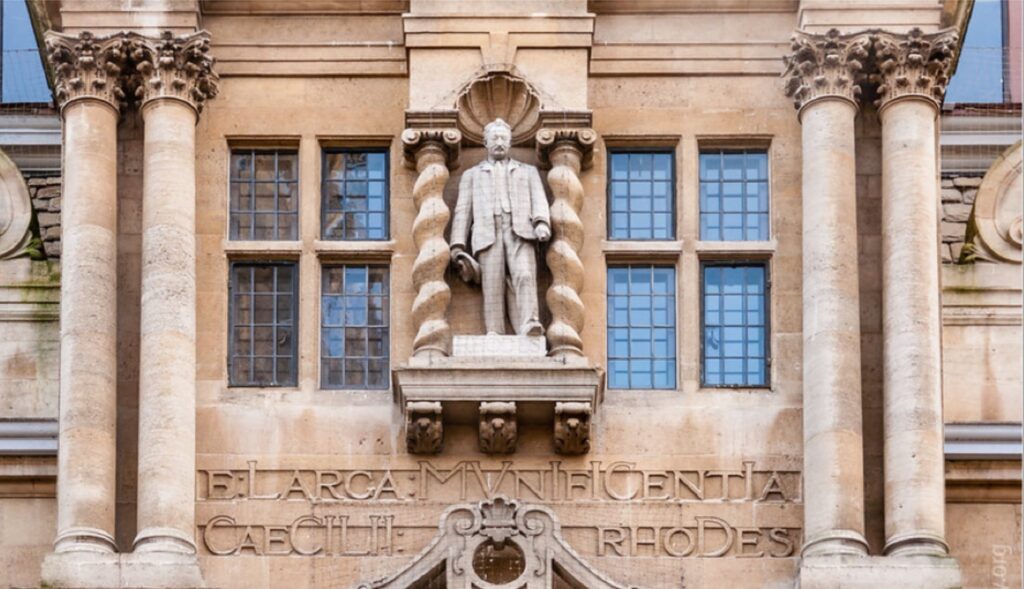

Arguments that support the protection of statues in the calibre of Cecil Rhodes are futile. Imagine if you were a black student studying at Oriel College (of which there are few, another layer to the multi-faceted dynamic of structural racism in the UK), and as you enter your place of study you see a white supremacist looking down at you. Effigies that celebrate the lives of men who committed abhorrent crimes cannot continue to stand on a pedestal. If they do, they serve to validate the views of white nationalists who revere former oppressors of black people. This grim reality was highlighted by the far-right demonstrations seen in response to Black Lives Matter protests.

A continued toppling of statues has been met with little opposition from historians, academics, and sections of the public. But the significance of statue symbolism is much more acute now because the discussion has become dichotomised. Those who idolise Winston Churchill or Robert Baden-Powell fear that their national story is being stripped away from them. Moreover, the developing TV ‘culture war’ has further entrenched a level of polarity in the UK. Focussing on cancel culture within media institutions not only conflates anti-racism with the loss of what some people perceive to be invaluable artefacts of British television, but it is perceived by critics to detract from the key racial justice issues at hand.

“No one is denying Churchill’s hugely influential role in World War II, but people are unwilling to accept that he was a racist”

This conflict over British culture is highlighted by previous desecrations of statues. For example, Winston Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square was defaced after May Day celebrations in 2000. The recent vandalising of this monument is not something unique to this moment in time. Where were his loyal protectors when white people were defacing his statue? Fascists found an excuse to exercise their racism, buttressed by the comments of prominent politicians and public figures. No one is denying Churchill’s hugely influential role in World War II, but people are unwilling to accept that he was a racist, and was culpable for the deaths of millions of people in the Bengal famine. By ignoring the reasons as to why statues have been targeted in denouncing the actions of Black Lives Matter protestors, the likes of Keir Starmer and Boris Johnson have stoked racial tensions that are steeped in white nationalism.

Is there a solution? The removal of chauvinist totems is a start; statue felling is making history, not erasing it. Colston was tossed in to Bristol harbour, triggering an international re-appraisal of statues that memorialise racism and oppression, including King Leopold II, Christopher Columbus, and Captain James Cook. In addition, there have been campaigns to erect statues of significant black figures, resultantly diversifying icons that inform national identity. This would mark the beginning of an attempt to reverse the past negligence of black histories, altering narratives that have been dominated by empire.

A plausible solution is the proposition of ‘statue museums’ that educate people about the history of slavery, white supremacy, and structural racism. A prominent feature of online activism in the wake of the recent and continued Black Lives Matter protests has been a focus on altering state education and public perception of history. This could be a tool that is used on an individual level as well as a structural level, teaching people from a young age about Britain’s role in creating systems of oppression. A proposal such as this will enable the decolonisation of historical and sociological discourses, in turn reframing British and global histories.

The removal of racist symbols will only go so far in the fight against deep-rooted discrimination against non-white populations on an institutional level. Unfortunately, you cannot expect change from the British government, whose foreign secretary compared taking the knee, a symbolic act of solidarity, to a fictional TV show. From a government that has proposed another race inequality commission which is headed by Munira Mirza, someone who called institutional racism ‘a perception more than reality’. From a society which is more concerned about being labelled as racist than actually addressing racism.

As seen in the USA, the power of collective direct action has agitated change. However, these changes need to be systematic rather than cosmetic. Populist governments, such as those in power in the UK and the US, will only seek to appease the public and cater to perceived public will. As the wave of online activism reduces and recedes, it is important that the Black Lives Matter movement is not just a moment, as Labour leader Keir Starmer ignorantly asserted. There has to be a continued push for justice and equality that is no longer obfuscated by empty promises.

Header image by Harry Pugsley.