Porgy and Bess: an insight into Britain’s changing opera scene

George Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess has found a welcome home at the English National Opera’s London Coliseum. The epic 40-voice chorus leads you through an emotive 3-hour journey which grips from the outset. Filled with powerful performances from a talented predominantly black cast who lucidly portray the sometimes joyful, but often tragic chronicle of a disabled beggar (Porgy) and a troubled woman (Bess). Porgy strives to be Bess’ saviour, but her demons, realised through her relationships with abusive men and a particularly pernicious drug addiction, make this an impossible task.

Gershwin’s somewhat sensationalised characterisation of the poor black communities of the American south has been controversial from its inception; the stern (and radical, in the context of 1930s America) request by lyricist Ira Gershwin that all leading roles be played by black artists caused an initial backlash whilst in turn launching the careers of several African-American artists. Acceptance from the black community was not unwavering either. It was seen to perpetuate unwelcome stereotypes at a time when contrasting narratives were seldom produced. This is perhaps best exemplified by Harry Belafonte famously turning down the leading role of Porgy for the 1959 motion picture. (Though he had no problems starring in Carmen Jones which was not exactly a stereotype buster, as pointed out by James Baldwin, no less). The role was later accepted by Academy Award winner and civil rights activist, Sidney Poitier. I doubt they were too disappointed with their back-up.

With this in mind, Porgy and Bess was perhaps a brave venture for the ENO, especially in light of the highly criticised Hungarian State Opera’s rendition, in which the wishes of the Gershwin estate – to have a black cast – were not upheld. However, The English National Opera firmly divorced itself from any such controversy with an outstanding production that appropriately begins its stint in Black History Month.

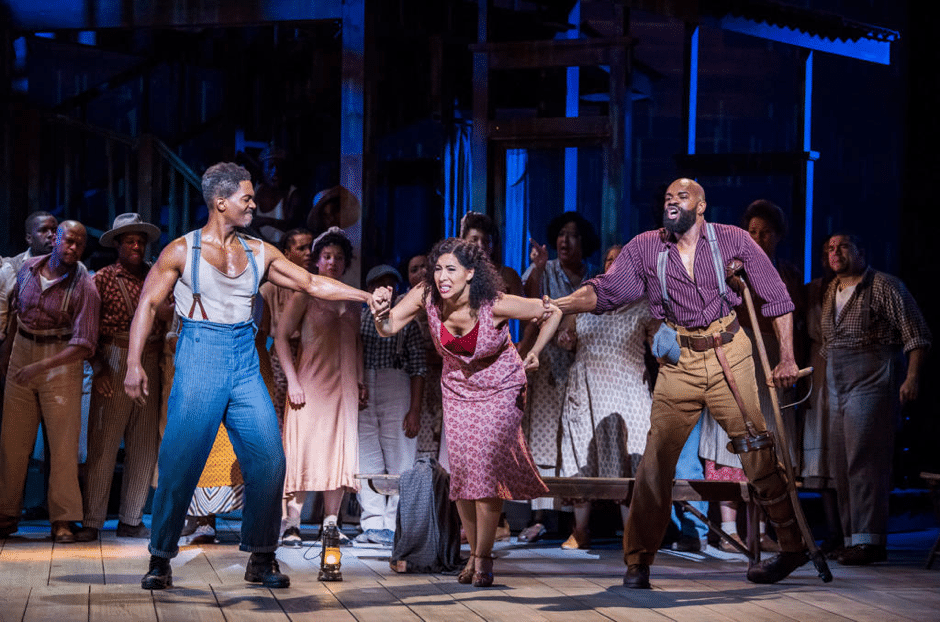

Still image from Porgy and Bess at the ENO by Tristram Kenton

Nadine Benjamin’s hair-raising rendition of ‘Summertime’ opens the show, introducing the prominent set designed by Michael Yeargon, and transports the audience from the cosy seats of the London Coliseum to the projects of South Carolina. The intimacy of the production is further supported by the lively and exciting choreography of the much-celebrated Dianne McIntyre. There is also an illuminating performance from Frederick Ballentine who portrays the evil yet somehow lovable Sporting Life, a drug dealer who continually entices Bess with his ‘happy dust’. Ballentine cements the marriage between Jazz and Opera and illustrates why Porgy and Bess is also hugely successful on the musical theatre scene. Nicole Campbell’s impressive and silky soprano beautifully reveals Bess’ insecurities and emotional trauma while Eric Greene’s rich baritone seemed to only grow stronger with every number. The two voices create a harmony that mirrors the surprisingly charming relationship that unfolds between the two juxtaposing characters.

In spite of the many individual highlights of the show, it was the group cohesion of the production which gave it intensity and its strength. Coherency was not a problem for the African-American, Black British and South African cast. Director James Robinson convincingly conveys the close-knit communities of the South which inspired George Gershwin. The immersive atmosphere was beautifully consolidated by a forceful orchestra led by a passionate John Wilson. Opting against putting a new political spin on the production – which produced varied results for past productions – proved to be an enlightened decision. The brief depictions of cruelty from the police (the only white characters), which featured in the original, felt unfortunately relevant. It seems that the slow pace of America’s ‘racial progress’ will keep Porgy and Bess timeless as much as Gershwin’s genius.

With War Requiem up next for the ENO and Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel (which has a solely female focus) later on in the season, this production of Porgy and Bess should not be perceived as an aberration, but part of the future of Britain’s changing opera scene. This is a performance for the opera virgin as well as the Madame Butterfly-loving veteran and could bring either audience member to tears. If you, like myself, never thought you would enjoy an opera, please allow Porgy and Bess to change your mind.

Porgy and Bess is showing until November 17th.

https://www.eno.org/whats-on/porgy-and-bess/?action=book

Tayo Lewin-Turner is a History undergraduate at the University of Bristol and his writing on Bristol's colonial past has been published by both Bristol 24/7 and bristolmuseums.org. As BME Officer, he has also worked extensively to improve the university experience for black students at the University of the West of England.